Abstract

A parser without grammar was implemented with neural sequence memory. It parses part-of-speech (POS) sequences represented on the sequence memory to create parse trees. It groups frequently occurring POS pairs in the sequence into a binary tree. For the syntactic category of the parent (root) node of a binary tree, it used the POS inferred from the preceding and following POSs, enabling the construction of higher binary trees from pairs of a parent node and a POS or another parent node. Experiments with artificial grammar have shown that the mechanism is capable of primitive parsing.

Introduction

Human languages are known to have constituent structure [Anderson 2022], which is a recursive (tree-like) structure of constituents. The constituent structure is also thought to be the basis for compositional semantics [ibid.]. In natural language processing, parsers with manually constructed grammars have been used to construct constituent structure from word sequences. As manual grammar construction is costly, attempts have also been made to automatically construct grammar (grammar induction) and to build parsers without grammar (unsupervised parsing) [Tu 2021][Mori 1995][Kim 2019]. Since humans learn their native language without explicit grammar instructed, it is not desirable to provide explicit grammar in cognitive modeling. Recent language processing systems based on deep learning have shown remarkable performance in applications. While they do not require explicit grammar, it is not clear whether they use hierarchical constituents or whether compositionality is properly handled. Thus, creating a model that builds constituent structure (parses) without explicitly providing grammar would contribute to research on human cognitive models, and implementing such a model in neural circuits would make it more biologically plausible.

Based on the above, a neural circuit that constructs constituent structures (parses) from part-of-speech (POS) sequences was implemented and is reported below.

Method

A mechanism to construct a tree structure on sequential memory implemented by neural circuits was devised. This mechanism creates a binary tree with frequently occurring POS pairs as child nodes. As the syntactic category of the parent node of a binary tree, it used the POS estimated from the POSs (categories) preceding and succeeding the tree, to construct a higher-level binary tree from a pair of a parent node and another POS or parent node.

Sequence Memory

Neural sequential memory was used. The memory used one-hot vectors as the internal states of the sequence, and a mechanism to store the sequence through associations between internal states and mutual association between input patterns and internal states. Associations (association matrices) are set up by a single stimulus exposure (biologically corresponding to one-shot synaptic potentiation). Similar mechanisms have been reported as the competitive queuing model [Bullock 2003][Houghton 1990][Burgess 1999]

Estimating Syntactic Categories

A POS was used as the syntactic category of the parent node of a binary tree. The POS is inferred from the POSs before and after the tree. For this purpose, a learning model was used to infer a POS from the preceding and following POS. As it is similar to what is known as the CBOW (Continuous Bag of Words) in language models such as Word2Vec, it will be referred to as CBOC (Continuous Bag of Categories) below.

Parsing Algorithm

- Read words up to the end of the sentence (EOS) and look up a dictionary to find POSs of the words to create one-hot vectors representing the POSs.

- Memorize POS vectors in the sequence memory.

- For each consecutive POS pair (head|tail), the activation value is calculated (see below) and assigned to the tail node.

- Repeat the following:

- For the sequence memory (tail) node with the maximum activation value, a new sequence memory node n is set for the parent node of a binary tree, whose child nodes are the tail node and the preceding node (head).

- A POS vector is estimated by the CBOC predictor from the two POS vectors associated with the nodes before and after the head and tail nodes, and is associated with n.

- Set links between n and the previous and next nodes

- Set links between n and the constituent (child) nodes

- Regard (pre|n) and (n|post) as POS pairs to calculate the activation value of n and post.

- Set the activation values of child nodes head and tail of n to 0.

- Delete the sequence links set for the head and tail nodes.

The implementation of the algorithm is located on GitHub.

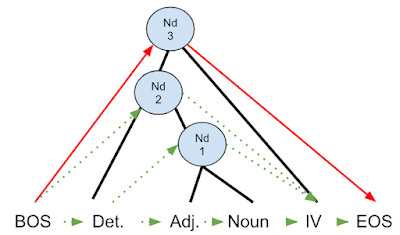

Figure 1: Parsing Example

BOS: Beginning of Sentence, Det.: Article, Adj.: Adjective,

IV: Intransitive Verb, EOS: End of Sentence

Categories given to parent nodes: Nd1: Det.+ IV ⇒ Noun,

Nd2: BOS+IV ⇒ Proper Noun, Nd3: BOS+EOS ⇒ None

Black lines: Constituent links, Red lines: Final sequence memory links,

Green dashed line: sequence memory links set initially or midway and deleted

Experiments

Input Sentences and Constituent Structure

Word sequences generated from a context-free grammar (see Appendix) were used as input sentences. To be precise, bracketed constituent structure strings were generated from a context-free grammar, and the parser used word sequences after removing the brackets. Notation for generation probability was used in the grammar, and sentences were generated based on the specified probabilities.

Evaluation Method

The edit distance between the input and output tree structures was used for evaluation. The input-output pairs in the bracketed tree forms were fed to an edit distance calculation tool. Non-terminal symbols were not given neither in the output nor in the output.

The following were used as activity values.

- Random values (baseline)

- Frequencies of bigram occurrence (number of occurrences ÷ total number)

- Bigram conditional probabilities p(head|tail)

Dataset

For cross-validation, a pair of datasets a and b, each containing 5000 sentences generated from the grammar with probabilities, and a pair of datasets A and B, each containing 10,000 sentences generated from a grammar without probabilities, were used. The maximum sentence lengths of datasets a, b, A, and B were 10, 11, 18, and 19, respectively.

Figure 2 shows the frequency of POS bigrams divided by the total number of data and the conditional probabilities (divided by 8 for comparison) for dataset a, sorted by the frequency.

Figure 2: Statistics of POS bigrams (dataset a)

Occ.: Frequency (number of occurrences/total number),

Prob/8: Conditional payment accuracy p(head|tail)/8

Learning

POS occurrences were counted from the generated sentences (Figure 2).

Note: Preliminary experiments have shown that both frequency of occurrence and conditional probability can be approximately approximated by perceptrons. However, both theoretically and practically, it is easier and more accurate to use simple statistical values so that there is no point in using neural learning.

A perceptron with one hidden layer (with PyTorch) was used as the CBOC predictor, and the mean squared error was used as the loss function (after having tried the cross-entropy error). The number of training epochs of the learning device was set to 20.

Results

Cross-validation was performed on each dataset pair. Namely, the system tried to parse the sentences from one of the datasets using the statistics and CBOC model obtained from the other dataset. The input and output trees were compared using an edit distance calculation tool. The cross-validated mean edit distance per word is shown in Table 1. In all datasets, using conditional probabilities as the criterion (activation values) for grouping performed better than using absolute frequencies.

Table 1: Edit distance

| Activation values | Random | Frequency | Conditional Probability |

| Grammar with Probabilities | 1.14 | 0.76 | 0 |

| Grammar without Probabilities | 1.34 | 0.79 | 0.65 |

For datasets based on probabilistic grammars, using conditional probabilities as activation values resulted in correct answers. For datasets based on grammars without probabilities, using conditional probabilities as activation values did not necessarily yield correct answers. For example, the following error occurred:

Correct answer:{{Det {Adj N}} {Adv IV}}

Prediction:{{{Det {Adj N}} Adv} IV}

While it is correct to group Adv:IV first, as its bigram frequency is the same as PN:Adv in the grammar without probabilities, PN:Adv{Det {Adj N}:Adv was grouped first (the estimated category for {Det {Adj N}} should be PN).

Conclusion

Incorporating prior knowledge about binary trees into a neural circuit model enabled parsing depending on the nature of the grammar that generates the sentences. It is to be verified whether natural language sentences have the same properties as the artificial grammar used here. The use of a parsed corpus such as Penn Treebank [Marcus 1999] would be used to investigate the statistical properties of the grammar and the applicability of the current method. For research aimed at language acquisition, CHILDES Treebank [Pearle 2019] based on a CHILDES corpus [Sanchez 2019]) could be used.

The current report does not compare performance with previous research. Since the ways of using and comparing trees in existing research are not uniform, it is necessary to reproduce (re-implement) the previous methods and align the conditions for strict comparison.

The current report deals with relatively simple sentences in context-free grammar. Extra mechanisms may be needed to parse sentences that include conjunctions, and sentences with multiple clauses. Even among sentences with a single clause, sentences containing prepositional phrases are to be examined. Furthermore, dealing with phenomena such as gender and number agreement would require adding grammatical attributes for those phenomena.

While POS sequences were provided as input in this report, it is ultimately desirable for a human cognitive model to be able to derive syntactic structures from acoustic input. Between the acoustic and POS levels, categories such as phonemes and morphemes are assumed to exist. Regarding phonemes, it is thought that categorization of acoustic signals into phonemes is learned in the native language environment. For extracting morphemes from phoneme sequences, statistical methods [Mochihashi 2009] and mechanisms based on patterns of non-phonemic attributes (accent, stress, etc.) can be employed. I have conducted a simple preliminary experiment to derive POS-like categories from word sequences, and confirmed that it was possible.

Considering this attempt as cognitive modeling, its biological plausibility (i.e., whether there is a corresponding mechanism in the brain) would be an issue. In the human brain, parsing is said to be carried out by Broca's area in the left hemisphere, and thus, it is thought to be primarily a function of the cerebral cortex. Since parsing is a process of time series, the cerebral cortex has the ability to handle time series, perhaps with sequence memory. Note that the brain's syntactic analysis is automatic (it does not require conscious effort). From an evolutionary perspective, it would be natural to think that human parsing evolved from a general-purpose mechanism of the cerebral cortex. The basic algorithm in this report consisted of grouping consecutive pairs that frequently occur and suppressing grouped "lower patterns." While it seems to have a cognitive advantage in that it directs attention to pairs of frequent patterns, neuroscientific research is needed to determine whether such a mechanism exists in the brain. Note that the combination of consecutive pairs is called ‘merge’ in generative linguistics, and is considered to be the fundamental process in syntactic processing.

One direction for future research is to link constituent structure with semantic representations to enable the compositional treatment of meaning.

References

[Anderson 2022] Anderson, C., et al.: Essentials of Linguistics, 2nd edition, eCampusOntario (2022)

[Tu 2021] Tu, K., et al.: Unsupervised Natural Language Parsing (Introductory Tutorial), in Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Tutorial Abstracts (2021)

[Mori 1995] Mori, S., Nagao, M: Parsing Without Grammar, in Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop on Parsing Technologies, 174–185. Association for Computational Linguistics (1995)

[Kim 2019] Kim, Y., et al.: Unsupervised Recurrent Neural Network Grammars (2019). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1904.03746

[Bullock 2003] Bullock, D., Rhodes, B.: Competitive queuing for planning and serial performance. Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks, MIT Press (2003)

[Houghton 1990] Houghton, G.: The problem of serial order: A neural network model of sequence learning and recall. Current research in natural language generation (1990) https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:59675195

[Burgess 1999] Burgess, N., Hitch, G. J.: Memory for serial order: A network model of the phonological loop and its timing. Psychological Review, 106 (3), 551–581 (1999) https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.551

[Sanchez 2019] Sanchez, A., et al. childes-db: A flexible and reproducible interface to the child language data exchange system. Behav Res 51, 1928–1941 (2019) https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1176-7

[Pearle 2019] Pearl, L.S. and Sprouse, J.: Comparing solutions to the linking problem using an integrated quantitative framework of language acquisition, Language 95, no. 4 (2019): 583–611. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48771165, https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2019.0067

[Marcus 1999] Marcus, M.P., et al.: Treebank-3 LDC99T42. Web Download. Philadelphia: Linguistic Data Consortium (1999) https://doi.org/10.35111/gq1x-j780

[Mochihashi 2009] Mochihashi, D., et al.: Bayesian Unsupervised Word Segmentation with Nested Pitman-Yor Language Modeling, in Proceedings of the Joint Conference of the 47th Annual Meeting of the ACL and the 4th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing of the AFNLP, 100–108 (2009)

Appendix

Context-free grammar used

Rules with : to the right of the leftmost category symbol are phrase structure rules, and rules with - are lexical rules.

The decimal value on the left indicates the probability that that rule will be selected among a group of rules that have the same leftmost category. For rules without specifications, the probabilities were determined by subtracting the specified probabilities from 1 and equally distributing the remaining probability.

S: NP + VP

NP : It + N1

N1 : Adj + N1 0.2

N1 : N

NP : PN

VP: Adv + VP 0.2

VP : IV

VP: TV + NP

Det - le, a

N - n1, n2, n3

PN - Pn1, Pn2, Pn3

Adj - adj1, ad2, adj3

Adv - av1, av2, av3

IV - iv1, iv2, iv3

TV - tv1, tv2, tv3